Battwa Lessons

In 2004, we were honored to spend time with the Battwa people, whose ancestral home is in the Impenetrable forest of Western Uganda and Eastern Congo. We were invited to do a spiritual assessment by the medical missionaries who were the sole medical care for the Battwa. The Battwa had been removed from their homeland for the international environmental community to establish a ‘peace’ park to protect the mountain gorillas. Even though the Battwa had cohabitated with the gorilla since before time, they were now seen as a threat and removed from their homeland, and the people were dying at an alarming rate.

In 2004, we were honored to spend time with the Battwa people, whose ancestral home is in the Impenetrable forest of Western Uganda and Eastern Congo. We were invited to do a spiritual assessment by the medical missionaries who were the sole medical care for the Battwa. The Battwa had been removed from their homeland for the international environmental community to establish a ‘peace’ park to protect the mountain gorillas. Even though the Battwa had cohabitated with the gorilla since before time, they were now seen as a threat and removed from their homeland, and the people were dying at an alarming rate.

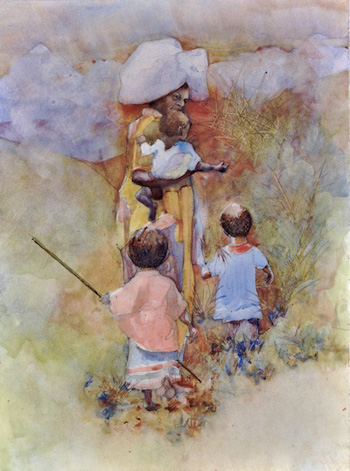

They carried drums everywhere and would stop everything at any moment to laugh, sing, and dance to the beat. Their caregivers hoped that, as a part of a larger medical concern, our spiritual assessment might shed some light.

“When you chose independence over relationship, you became a danger to each other. Others became objects to be manipulated or managed for your own happiness. Authority, as you usually think of it, is merely the excuse the strong use to make others conform to what they want.”

—William Young, The Shack

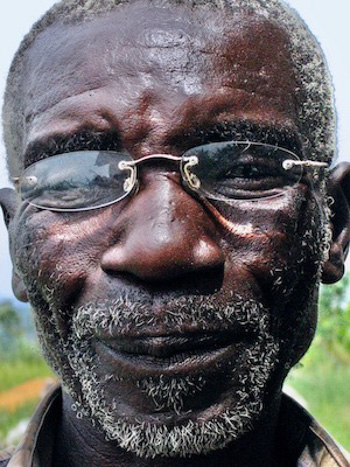

The Battwa granted us an interview with their elders. Among other enlightening treasures, their view of individualism was particularly insightful.

To prepare for our interview, they organized themselves, seated on the ground, men and women elders together in a half-circle with the spokesperson, James, the ‘head man,’ seated separately at the center of the half-wheel. Facing James, with the elders behind him, was me and their interpreter side by side. Being warned of their predisposition to please, I constructed my requests for stories to be entirely open-ended with no discernable right or wrong answer to the best of my ability.

As I asked James to tell me a story about how (fill in the blank) came to be, he would turn his back on me and repeat the question to the elders. They would debate the answer until they had agreed on the answer. When they arrived at a consensus, James would turn to face me again and deliver their response. An entirely egalitarian process.

In response to my inquiry about their process, they explained they are first ‘the people’ and survive only when all share, when they hear all voices, so all are safe. They apparently have a concept of the individual, but only as the ‘outlaw,’ who is the one who takes more than their share. The outlaw takes for themselves what belongs to the people. The Battwa are typical of what I understand about other historical aboriginal groups of hunter-gatherers whose very survival depends on the willingness of each to submit to the welfare of all.

Individualism has not always been the standard for Western society. The admiration and elevation of the individually powerful over the weaker to the detriment of the whole are disgraceful and are an evolutionary dead end. When personal power and the privilege that comes with it are the standards for a position in society, we live in a failed culture.

Individualism is a myth. I, me, and mine is the universal creed and concern of ditch dwellers, the only living inhabitants of the ditches.

Individualism is a myth. I, me, and mine is the universal creed and concern of ditch dwellers, the only living inhabitants of the ditches.

• • •

I asked James, through the interpreter at another gathering, to tell me a story about how things came to be, and he said,

“The Great Creator Spirit created all things, and when She had finished, She called all the people to herself and gave gifts to each people group. She realized when done that She had forgotten the Battwa. Apologizing to them, She gave them the only thing left, that mountain over there we are sitting near but no longer sit on.”

That mountain was their gift from the Spirit, an act of Love. Their forever connection to Her and the evidence they are loved by Her even though they had once been forgotten. The mountain rooted them in Her, their spiritual rootedness. Like the Hebrews, even to this day, are tied to the land that they believe YHWH gifted to them, so too are the Battwa. (Indigenous peoples of the world over have experienced the same. The first peoples of the Americas, whose numbers have been estimated at 14M in 1492, were reduced to 237,000 by 1900 William M. Denevan writes that, ‘The discovery of America was followed by possibly the greatest demographic disaster in the history of the world.” Research by some scholars provides population estimates of the pre-contact Americas to be as high as 112 million in 1492, while others estimate the population to have been as low as eight million. In any case, the native population declined to less than six million by 1650…At the turn of the twentieth century, the total number of Native inhabitants living in the entire Western Hemisphere had declined to 4-4.5 million. In 1800, only about 600,000 Indigenous people remained in the coterminous United States. By 1900, the Indigenous population in this country reached its lowest point of about 237,000 people.’ —David Michael Smith University of Houston-Downtown. Appears to be a pattern for humans of European descent.)

For the Battwa, separated from the land, their spiritual root had been severed, and they were set adrift. Their understanding of who and what they were, along with the meaning of their lives, was vanishing.

The People, the meaning of Battwa, were rounded up by a very well-intentioned, misguided international community of neo ‘liberals with an environmentalist agenda that they believed was significantly more important—the protection of the Mountain Gorilla from poachers—when compared to the emotional, mental, and spiritual well being of the Battwa. When the people attempted to return, I was told some were shot.

• • •

A very gentle people, in my experience, were mostly compliant with the Europeans who had ‘generously’ offered to teach them to be farmers instead of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers. The difficulty no one seemed to notice was that the Battwa had no future tense in their language. And why would they? The people never built a structure, so they had no villages. They traveled in order to feed. When the supply was exhausted in one area, they changed location, and when they stopped for the night, they would pull the large leaves of the plants over themselves for protection from the rain. They lived like the Mountain Gorilla.

So, when the Europeans brought them a mated pair of goats that, in the future, would become a herd, they had a goat roast. When they brought beans for planting, they ate beans.

So, when the Europeans brought them a mated pair of goats that, in the future, would become a herd, they had a goat roast. When they brought beans for planting, they ate beans.

• • •

The natives among whom the Battwa were deposited were not kind to the people. They only knew them as the little, dirty, naked people who sneaked around in the dark forest and had spears. Although the natives lived adjacent to the ‘Impenetrable Forest,’ they had little to no contact with them. There was a Christian church building near the Battwa ‘farm.’ A missionary had convinced a few of them to say they were Christians and told them they needed to come to church, and so they did. But the natives disapproved and made them sit in the back of the church because they said they smelled bad. They quit going.

Based on his experience as a holocaust survivor, and a Nazi concentration camp survivor, Frankle taught that people die when their lives no longer have meaning. The Battwa were dying at an alarming rate. The medical missionary who asked Claire and me to come thought there was real danger of their extinction. There were so few of them. Their gift from the Creator Spirit, the mountain, and the forest were gone. They must have wondered if She was gone as well, or perhaps She just didn’t Love them anymore.

Based on his experience as a holocaust survivor, and a Nazi concentration camp survivor, Frankle taught that people die when their lives no longer have meaning. The Battwa were dying at an alarming rate. The medical missionary who asked Claire and me to come thought there was real danger of their extinction. There were so few of them. Their gift from the Creator Spirit, the mountain, and the forest were gone. They must have wondered if She was gone as well, or perhaps She just didn’t Love them anymore.

We stayed there among the ‘People’ for three weeks, and as the time drew near for us to go, James, the ‘head man,’ asked Claire and me to stay, saying, “The ‘People’ want you to stay so that we may have more of these spiritual talks, and if you agree we will build you a shade where we would all sit and talk together, and there will be eating and dancing.” But we are Ma-zoon-goo, the name they gave to the early Christian missionaries, which means ‘the people who travel all around’ or ‘the people who don’t stay.’